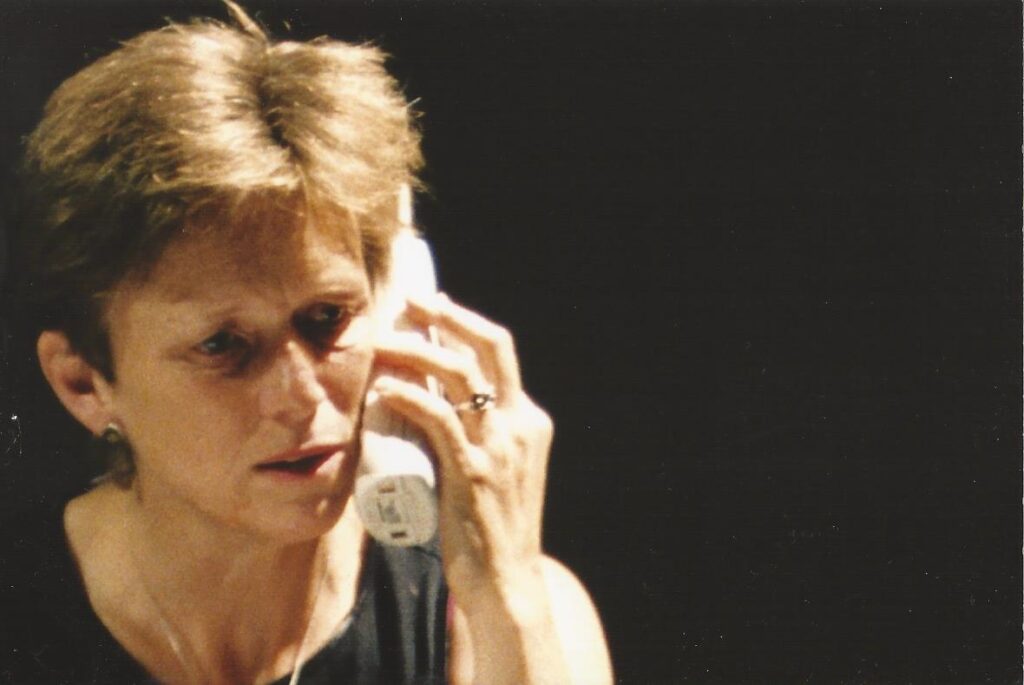

An evening of six short plays written for Obie-Award winning actress Louise Smith. Six plays, six female characters and the masks they wear to conceal their true identities. The plays are The Human Voice, a mistress saying good-bye to her lover for the last time; Runaway Honeymoon tells the tale of a slave couple where the light skinned wife pretends to be her husband’s white world; The Diva Makes Her Entrance takes place back stage in the waning days of burlesque; Mother Love is the interrogation of a murderess mother; and The Talking Mask where aging woman morns the fading of youth and beauty.

Cast & Crew

A co-production with Pillsbury House Theatre

first presented at Pillsbury House Theatre in 2004

Written and directed by Carlyle Brown

Music by Oliver Lake

Cast

Louise Smith as Ensemble

James Austin Williams as Ensemble

Gwendolyn Schwinke as Ensemble

Lori M. Neal as Stage Hand

Molly Sue McDonald as Violinist

Designers

Lighting design by Mike Wangen

Press

Women’s Mask Force

by Matt Di Cintio, City Pages, May 26 2004

One of my favorite theater memories is Carlyle Brown dancing to the Manhattans’ “Shining Star” in his show The Fula from America. The song celebrates his arrival in Freetown (the capital of Sierra Leone–and a metaphor to boot!), and though not the climax of his one-man show, the number marks a significant destination on his journey. His new work, Talking Masks, co-produced by Pillsbury House Theatre and Carlyle Brown & Company, has no such coup of theatricality. Nor does it need one.

The work consists of six short plays, all centered on the theme of identity–masks we wear, masks we are forced to wear. Also in common: All were written for Obie-winning actor Louise Smith. It’s clear to see why Brown is so fond of Smith’s work, which here is committed, unflinching, and deliberate. She plays the central character in each of the six plays, from a modern murdering mother to a 19th-century slave. The range can lend her performance a schizophrenic feel, but only because she’s compelling each time. She may be gentle and forlorn in “The Human Voice,” but then she is cunning and selfless in “Runaway Honeymoon,” silent and painfully mysterious in “Mother Love.” To add to the to-and-fro, the one-acts are linked by new violin music (played coyly by Molly Sue McDonald) from renowned jazzman Oliver Lake, the dissonance of which ties the plays to their common theme.

“The Human Voice,” the evening’s first playlet, was adapted by Brown from Jean Cocteau, and was the piece that first brought this playwright-actor team together. This character has been Smith’s for a while, and she knows it. She’s a mistress being dumped over the phone. The conversation is shown mostly one side at a time. Imploring and consoling her married lover (James A. Williams, who compels throughout with understated firmness and constancy), Smith keeps her pitch just shy of hysteria. Her character is hardly true enough to herself to indulge in the melodrama of romance (talking mask #1, for those keeping score). To watch the breakup is the kind of voyeurism you feel when friends are arguing bitterly during a party. You’re embarrassed for them, but you don’t dare leave the room: You have to watch.

“Runaway Honeymoon” is based on a true account of a couple who escaped slavery thanks to the wife’s pale skin. They evade the suspicion of a debutante (Gwendolyn Schwinke) because the slave woman (Smith) is dressed as her husband’s master. Williams does well to give his character a humanness that goes beyond a slave’s eyes-to-the-ground posture. There are enough unabashed racial slurs and grand frills on Schwinke’s dress to make of the play a minstrel show turned on its ear. So is identity a political, social issue? With that question lingering, “White Girl from the Projects” follows. It’s pretty much what you’d expect, and if Smith doesn’t quite convince us that she is from the projects, her performance of that “mask” is still enough for us to be empathetic to her racial roadblock. Schwinke is at her best in “The Diva Makes Her Entrance” as an insecure burlesque starlet. I wasn’t sure if the divas’ ending dance number was supposed to come across as parody, but at least the journey of Schwinke’s starlet is clear: She moves from whining, backstage shame to limelit poise. Though the final and abstract scene, “The Talking Mask,” recalls the mask work of novice performers, this is not the show’s overall impression. The poetic language still rings true and fresh, and there will always be something haunting about the neutral mask moving in space. It’s that fixation that drives home the evening: Humanity lingers when the human goes away.

Brown directs his work with subtlety. He has led his actors to faithful and full interpretations of his text, and more importantly, to unreserved performances. In his program notes, the playwright acknowledges women in his life for their strength and generosity. But in none of the six pieces is there anything elegiac; there are no odes to femininity, no Important Women bioplays. What the evening does have is sharp, economic writing (times six) coming from poetic mouths. That’s the way he and Smith celebrate women. Shining stars indeed.

Review – Talking Masks – Carlyle Brown & Company and Pillsbury House Theatre – 5 stars

by Matthew A Everett, May 15, 2004

One of the more daunting tasks for a male writer, at least this male writer, is to take on the assignment of writing roles for women. Not just our perception of women, but as true an approximation as we can muster, never having lived in their skin. Something that a skilled actress would find worthy of her time and talents. At the root of it, there’s always something else as well. I was reminded of it by an actress during a workshop of a musical I was working on recently. On a break she came up to me and said, “As I was reading the script, getting ready for rehearsal today, it struck me, ‘This guy must have been raised by some pretty remarkable women.’” On some level, when men write female characters well, it is a tribute to the women who gave us life and the women who raised us, the women we admire, the women without whom we wouldn’t be men at all.

Carlyle Brown’s play “Talking Masks,” receiving its world premiere at Pillsbury House Theatre as a joint production with Carlyle Brown & Company, is such a tribute, and a very fine tribute at that.

The evening is collection of six very different scenes, all spotlighting the talents of Obie Award-winning actress Louise Smith in a half-dozen widely disparate roles – the abandoned “other woman,” an escaped slave masquerading as a white man, a white woman who identifies as black, a burlesque diva, a meek but murderous mother, and a woman coming to grips with her true face as she begins to age.

Though the script was written with her in mind, Ms. Smith is not alone on stage by any means. Only one of the scenes is a solo piece. In all others, she is part of an adept trio which features the wide range of skills offered by James A. Williams and Gwendolyn Schwinke.

There’s a reason that Pillsbury House Theatre was recently lauded as the Best Theatre for New Work in the City Pages. They give a play the kind of staging it needs. The play just previous to this in their current season, Caryl Churchill’s “Far Away,” asked its audience to fully enter the dark and peculiar world which was presented. Carlyle Brown’s direction of his play “Talking Masks” takes the opposite approach.

The audience is never allowed to forget that they are observing theater, that they are taking part in a collaborative experience. The scaled down production values put the words and the actors on full display, and insists that the audience be equal participants, bringing their imagination to bear to fill out the details of the world presented on a black stage floor, with only dark curtains as a backdrop. The title of each sequence is presented on a sign resting on an easel, always in view as the action takes place. The play has its own live soundtrack, composed for the production, ably performed by Molly Sue McDonald on violin in full view of the audience. Again, we are not encouraged to lose ourselves in the music and merely listen, we must observe. Even the scene changes are performed. Stage hand Lori M. Neal is not a faceless worker scurrying around in the dark who we are not supposed to see. She takes her time, in half light, and we sense even her personality in the time between each episode. In the burlesque sequence, the black curtain is deliberately parted and left open so we can see the unadorned backstage world of the theater as well. The idea of theater as an art form is stripped down to its essence and laid before us. Rather than feeling cheated by a “lack” of production values, this approach makes the evening that much more engaging.

Nothing is what you expect it to be. “The Human Voice,” which opens the evening, seems as if it will be a one-sided phone call monologue. Before it is over, the call has been handed back and forth between two characters, and interrupted by a third party, before returning again to where it started. During that time, we get a clear picture of two fractured relationships, and the inklings of a third. All accomplished with almost no instances in which any character responds to another directly.

The high comedy of the next segment, “Runaway Honeymoon,” never quite lets you forget that the audience is also being presented with a quite clever take on the roles played by white and black, man and woman, husband and wife, master and slave. The liberal use of the word “nigger” prompted an unusual response in this audience member. Even though I knew that the two white actresses had full “permission” to use the word, coming as it did from the hands of an African-American writer and director, it was never something I was comfortable with, despite the comedy which still allowed me to laugh. The word remained loaded. Still, this scene was one of the most charming, funny and uplifting of the evening – a strange mix indeed.

“White Girl From the Projects,” Ms. Smith’s solo turn of the evening, was full of brash and surprising humor, and humanity. The title says it all. It’s the theatrical equivalent of jumping off a cliff without a net, and Louise Smith not only lands squarely on her feet, she does it in grand style.

“The Diva Makes Her Entrance” is most notable for the trick of carrying on two plays simultaneously. While our primary attention is focused backstage on the two burlesque performers preparing to go on, at the same time James A. Williams, as master of ceremonies, is performing a piece of his own onstage, and never misses a beat. Though I couldn’t tell you exactly what he was doing, as I was seated on the opposite end of the auditorium from him, I’ve no doubt that those seated in front of him were enjoying an entirely different show.

The apparent police interrogation which is the setup for “Mother Love” turns out not to be quite the point of the scene at all. It is the one piece of the evening that I couldn’t quite figure out, and yet it’s the one that I continue to mull over a day later.

The close of the evening, “The Talking Mask,” is perhaps the most theatrical turn of all – all three cast members in dark clothing, and a mask which seems to have a life of its own. Louise Smith’s manipulation of the mask often seems to defy gravity, and James A. Williams and Gwendolyn Schwinke interact with the mask in a way that makes us believe it, too, is human. It is a wonder to watch.

By setting the bare bones of theatre and all its tricks out in front of the audience, Carlyle Brown & Company make our appreciation of it that much greater.

“I was raised by three women, my mother and my grandmother and my aunt, and if these stories came from anywhere, they came from them,” Carlyle writes in the program, concluding with, “And so it is my hope, as a writer and a son, that all of these short plays will have something to say to every woman.”

I can’t speak for women, but the playwright/director and his collaborators certainly said something to me – and I’m glad I had the chance to hear it. I recommend you do, too.

Layers of collaboration in ‘Talking Masks’

by Marianne Combs, Minnesota Public Radio, May 24, 2004

All theater productions are by their very nature collaborations, but writer and director Carlyle Brown’s latest work, “Talking Masks,” seems to go further than most.

It tells the story of six women in six vignettes. He worked on the scripts with actor Louise Smith, who plays all the main characters. Brown says he was excited about the material, but he wanted to do something special to bridge the gap between each story. Everyone’s seen these plays where we watch stage hands move the furniture in the dark,” says Brown. “I like to call them ‘the acme moving company’s production of Between the Scenes.’ We wanted those scene changes to be interesting.”

Brown took his show to Pillsbury House Theater. It produces a few plays in its space in Minneapolis each year.Co-Artistic Managing Director Noelle Raymond says in order to keep from going dark for long periods of time, Pillsbury collaborates with other theater companies in town that don’t have their own space.

“It simultaneously allows Pillsbury to produce more work, maintain relationships with artists in the community, and to explore new ways of creating work,” says Raymond.

So a second collaboration was born. Then, as luck would have it, nationally reknowned jazz composer and performer Oliver Lake was in town on a McKnight Foundation Fellowship. He approached Pillsbury House Theater looking for a residency. Carlyle Brown suddenly had a composer at his disposal to work on bridging the six vignettes with original music.

Oliver Lake goes over the music with Molly Sue McDonald. Before each scene, McDonald stands to the side of the stage and performs a piece that sets the tone for the story to follow. McDonald says she’s used to singing and acting on stage, but it’s rare that she plays her violin. This project is stretching her in new ways, which makes her nervous. She’s trying to think of it as another acting job.

“It’s another character in the play,” says McDonald. “It’s transitioning from one part of the play to the next and I’m interested in seeing what drama that brings, dramatically, working in a musical sense.”

Collaborations allow artists to pool their resources. But collaborations also impose limitations. Oliver Lake is a world-renowned composer, saxophonist, flautist and bandleader. He is a co-founder of the internationally acclaimed World Saxophone Quartet. Yet while Oliver Lake may be composing the music for the production, that doesn’t mean he gets to decide how it sounds.

“No, it wasn’t like that at all,” Lake laughs. “It was talking to Carlyle and Carlyle saying ‘It’s gonna be a violin.’ And actually we started off with two musicians; acoustic upright base and violin. So I originally wrote it for two instruments and then later he decided he wanted it to be one instrument, but he wanted it to sound the same way. I said that’s not possible!”

But sometimes limitations force artists to try new ideas that work even better. Writer and Director Carlyle Brown eliminated the bass player for financial reasons. He later realized that it made more sense for the music that bridges these scenes about six different women to be performed by a single woman.

Brown says he’s particularly appreciative of the opportunity to work with both Oliver Lake and Pillsbury House Theater. He says working with like minded people speeds up the rehearsal process. And he says working with people he respects drives him to do better.

“I wake up usually about 3 or 4 times in the middle of the night wishing I was never born,” says Brown. “But you know on the whole it’s been a very fulfilling experience in ways which I still have to process. I mean just working as an artist with these people is what one imagined working as an artist is about. I’m just as happy as a rat in a cheese factory!”

“Talking Masks” examines women’s lives

by Dwight Hobbes of Southside Pride, April 2004

The upcoming Pillsbury House Theatre/Carlyle Brown & Company collaboration on Brown’s “Talking Masks,” directed by the author and starring Obie Award winner Louise Smith, holds enormous promise. As a matter of fact, in addition to the already esteemed talents of Brown and Smith, the production boasts the talents of residency artist Oliver Lake, who will score the production. New Jersey-based globe-hopper Lake is a composer, saxophonist, poet and spoken word artist who can name, among a laundry list of impressive credits, a Guggenheim Fellowship, commissions from the Library of Congress and the honor of having his compositions preserved at the Smithsonian. Lake has performed through out the world, touring Japan, Australia and Europe in 1996 with The World Saxophone Quartet (as co-founder) and Trio Three. He has also performed and arranged for such diverse artists as Bjork, Lou Reed, Abbey Lincoln and Tribe Called Quest.

Lake got hooked up with Pillsbury House Theatre through his good friend actor-director-writer Laurie Carlos, whose work is well known to Twin Cities audiences. He had copped a McKnight Visiting Composer with the American Composers Forum Grant and was looking for an outfit to work with. “She put me in touch with several groups,” Lake recalls. “I contacted all of them and had this talk with Faye Price. And it looked like the residency would fit very well with her organization.”

“Talking Masks” is an evening of six short scripts that looks at life through the lens of women’s experiences. “Runaway Honeymoon,” drawn from slave narrative of William and Ellen Craft, recounts the escape of a husband and wife. Ellen was so “high-yellow” she posed as a White man traveling North with William as the slave. The protagonist of “White Girl From the Projects” grows up in a black, urban environment, resulting in one hell of a struggle for personal identity. In “Mother Love,” a mother is interrogated in a police station about the murder of her son. Brown is an expert storyteller and a compelling dramatist. The thought of such subjects in the hands of someone as gifted as Brown is enough to have theater-goers who appreciate strong drama practically slobbering on themselves. The night’s other titles are “The Human Voice,” “The Diva Makes Her Entrance” and “The Talking Mask.”

In the summer, Lake will work with youngsters who participate in the Chicago Avenue Project—an arts mentorship program that pairs neighborhood youth with professional artists to create original theater. Lake will help young playwrights develop plays using music. The plays will be presented under the title of “You Snooze – You Lose” on August 30 and 31. Lake will also work closely with the theater’s improvisational company, Breaking Ice, conducting spoken word/poetry workshops for the Breaking Ice Acting Company. Lake looks forward to working with the students. “I’m excited to see what happens,” he says. “Because it’s gonna [be great] to see the students I’m going to be working with. I have worked often with students before. In Tucson and other places. They were studying music, though. I like the idea of the difference. Of working with non-musical students. And designing music for their plays. It’s also a chance to create some spoken word with students.”